The board of the Century House Historical Society stands in solidarity for civil rights. We condemn police brutality against Black individuals and communities and the persistent systemic inequalities that continue to burden far too many.

We are an organization focused on education and the arts, and we want all of our visitors to feel fully welcome. We are grateful for the many vibrant contributions to our years of arts programming from poets, musicians, artists, and audience members who are Black, Indigenous, and people of color. In this time of acute grief and anger, we are thinking of you, and we value your truth and your voices.

As an organization with a historical mission, we acknowledge that centuries of prejudice and willful blindness leave lasting pain and disadvantage that require concerted, ongoing effort to redress. The everyday experiences of people from all backgrounds and walks of life weave together to make a fabric whose strength supports everyone in the community. While we do not suffer equally, any fraying or tearing of that fabric affects us all. Injustice – and change for the better – are neither inevitable nor accidental: they are the sum of actions and inaction by generations of individuals and institutions.

We are also humble in our awareness that we can and must do more to learn about and share with our audiences the perspectives of Black people in our community today and in the historical past. The region of the historic Rosendale cement district has been and continues to be home to the Esopus people, but since European colonization (initially by Dutch settlers in the late 17th century), and especially during the cement mining era which is the focus of our historical mission, it has been overwhelmingly populated by people of European descent. The rarity of Black voices in the local historical record reflects these demographics but also the marginalization experienced by people of color. As we consult historical records, we must always keep in mind the questions: Whose stories are we missing? Why? How can we do better to seek them out?

One of Ulster County’s most famous natives was Sojourner Truth, who was born into slavery in Swartekill (in modern Rifton, only a few miles from Rosendale) c. 1797 and eventually become one of the most courageous, eloquent and influential voices in the national movements for abolition of slavery, opportunities for freed Blacks, and women’s rights. In 1828 Truth won a dramatic court victory in Kingston (later a mining center as well) to free her young son from bondage. That same year saw the first mention of Rosendale’s natural cement industry in the Report of the Committee on Roads and Canals, rocks suitable for cement production having been discovered along the planned route of the Delaware and Hudson Canal in 1825. Truth’s story reminds us that Black people lived and labored in slavery in farms and towns throughout the cement region even as the region embarked on a new era of industrialization.

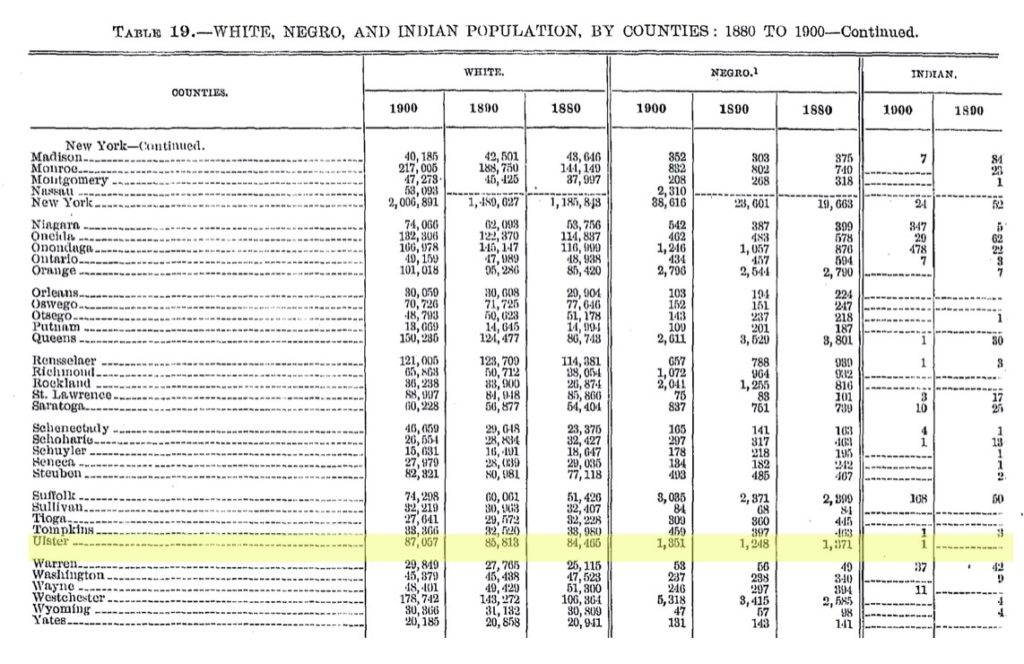

Direct connections between the history of Black residents and the history of the cement industry are harder to find. For example, board members are currently not aware of any records of Black men employed as miners. Rosendale cement was famously used in construction of the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty, among other landmarks, and the cement industry drew many immigrants to our region. The Black population of Ulster County enumerated by the 1900 census (one year after the peak of the cement industry) was 1351, about 1.56% of the population, so why weren’t Black people similarly drawn into opportunities in the cement industry? How many Black people were employed as coopers, canawlers, or in other professions connected to cement production? What can we learn about the experiences of Black people in the construction of buildings and monuments in New York City and beyond, which were built of Rosendale cement? More recently, we have photographic documentation of Black servants employed in the household of A.J. Snyder II, who operated the last cement manufacturing company in the region and lived at the Snyder Estate, which now hosts the Century House Historical Society’s museum and events. We don’t know these individuals’ names or stories. We have more questions than answers and much to learn.

We hope to showcase more historical records of the Black experience as well as contemporary Black voices in our future programming, and we hope you will join us in lifting up these stories.

[https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1900/volume-1/volume-1-p10.pdf , p 550]